Post-Colonial Identity Reflected In in Almaty Restaurants

America is, famously, the “melting pot” of cultures. In my 21 years of living there, I’d become accustomed to being able to try cuisine from nearly any culture, and expect to have a good experience, with delicious food that represents the best that country has to offer. So, when I came to Central Asia, I was quite curious to see the cultural influences of the local food. In Almaty, Kazakhstan, where I spent most of my time, I tried an ample amount of both Central Asian dishes as well as ethnic food served in local restaurants. What I found was a culinary culture that was a great reflection of Kazakhstan’s postcolonial identity: Central Asian and Western restaurants coexisting, seeming like two worlds at first but slowly starting to intermix.

Plov, an extremely popular Uzbek dish, served in both Uzbekistan and Karakalpakstan

Plov, an extremely popular Uzbek dish, served in both Uzbekistan and Karakalpakstan

The limited amount of preliminary research I did before my trip told me that the food I would eat in Central Asia would be a mix of both traditionally Central Asian dishes, as well as European dishes which came to Central Asia during the Soviet period. The food that my host family served me very much fit this, as I found myself eating both Central Asian dishes such as plov, beshbarmak, and lagman, as well as Russian-feeling hard-boiled eggs, doctor’s sausage (докторская колбаса,) and pelmeni. On the street, I found another division, between restaurants that served “Soviet-style” Central Asian and Russian food, and “foreign” restaurants that served either Westernized fast food or ethnic dishes. On practically every block, I could find at least one restaurant serving doner kebab or samsa, and another serving hamburgers and hot dogs. It felt at first like a hard line in the sand between these two groups, and I envisioned the rest of my food outings as either being at a local-feeling doner stand or at a Western-style, corporatized chain.

The “I’m” in Almaty (what McDonald’s, previously using Russian ingredients, has rebranded to after sanctions and supply chain issues)

The “I’m” in Almaty (what McDonald’s, previously using Russian ingredients, has rebranded to after sanctions and supply chain issues)

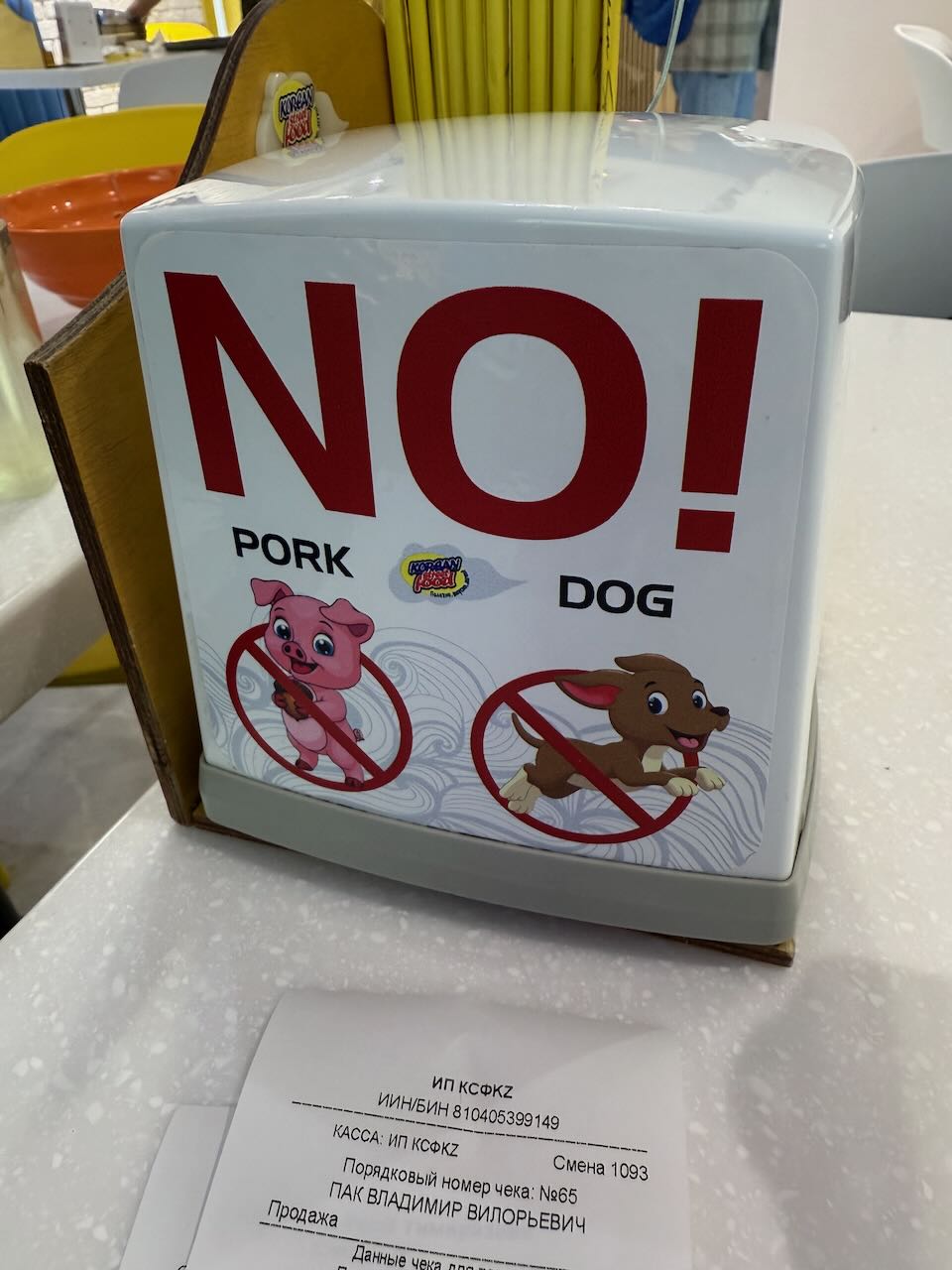

The longer I stayed in Almaty, however, the less these two styles of restaurant felt like two worlds. I stopped one day to get doner at a place called “Doner Na Abaya,” and immediately noticed the adjacent “Burger Na Abaya.” Both places were similarly decorated, and since the doner side was full, the employees at the burger side were happy to let me sit there. I soon discovered the start of some mutual culinary inspiration. Across the street from Kazakh National University, where I studied, is Gippo. Gippo is a fast food stand that also serves not only pigs in a blanket like you might find in America, but also “minisamsa,” bite-sized samsas served alongside the pigs in a blanket in the same cups. Another fast-food chain that I’ve really enjoyed in Almaty is Korean Street Food, which serves plenty of traditional Korean dishes such as kimchi, tteokbokki, and Yangnyeom chicken. Before going, I was curious as to how cuisine from a country that ate so much pork would be served in a Muslim-majority country where serving pork wouldn’t be economically viable. I got my answer when I sat down and noticed a sign on the napkin holder that read “NO PORK, NO DOG!” I ended up ordering kimbap, kimchi, Yangnyeom chicken, and «Корейские пельмени» (Korean pelmeni.) The kimbap and chicken were similar tasting to the Korean food I’ve eaten in America, but the pelmeni tasted exactly like any other pelmeni I would have eaten at my host family’s or at a local restaurant. This was such a surprise to me, and it felt to me like a conscious decision to have the pelmeni “feel local” to make the restaurant more approachable.

Said sign, kimchi, and kimbap from Korean Street Food

Said sign, kimchi, and kimbap from Korean Street Food

Even American fast-food chains which have made their way to Almaty have taken some influence from local culture for the sake of approachability. Kazakhstani KFC serves rice as a side, as well as a dish called “Twister Kebab,” which is fried chicken, French fries and some toppings wrapped in a wheat flatbread, or in other words, essentially a doner made with KFC chicken as the meat. A similar item is also served at Popeye’s, Wendy’s, I’m, and Hardee’s, although they don’t use fries, and have a tortilla as the wrapper. This “proto-doner” is so interesting to me. Many fast-food restaurants serve different items in different countries, such as McDonald’s serving poutine in Canada, but the fact that all of these American chains have standardized on an item that will gain them traction in Central Asia is so cool.

This blend of cuisines is something I’m all too familiar with as an American. American Chinese food, over the nearly 200 years that Chinese people have been immigrating to the US, has very much developed its own identity, with countless new dishes being created to be more palatable to the average American, and many others that existed in China but were only popularized when they came to America. Cashew chicken, for example, was created by David Leong, a Chinese-American restauranteur and World War II veteran who moved to Springfield, Missouri from Florida after a neurosurgeon on vacation visited the restaurant where he worked and was so impressed by his cooking that he begged him to move to his city. In the face of racism and attacks against his restaurant (which was broken into and robbed before it opened,) Leong created a dish that appealed to locals, blending the fried chicken they already loved with Chinese flavor. It was a smash hit. The California roll was created under similar circumstances. While its true origin is debated, most stories behind its creation share a common tenet: a sushi chef wanting to make dishes more appealing to Americans modifies the traditional roll by moving the rice to the outside (hiding the off-putting seaweed,) substituting raw fish for imitation crab, and adding avocado for texture. These dishes, not dissimilarly to the proto-doner and pelmeni served in foreign restaurants here, served to not only acquaint Americans with foreign tastes, but also served as a sign of respect towards the culture in which the restaurant was operating. Leong appealing to Missourians by serving them fried chicken showed them that he cared about their culture and was making conscious decisions to integrate into and be a part of their community.

Colonialism can also be a basis for culinary fusion in a similar way, with the Vietnamese bánh mì being a classic example. French colonial rule brought the baguette to Vietnam, which was eaten in a traditional French way until the dissolution of French Indochina split Vietnam in half. Without the French bringing in Western ingredients, the bánh mì was first created in Saigon. Mayonnaise and Vietnamese veggies replaced expensive cold cuts, and a classic was born. Over the next few decades, meat fillings such as pâté and pork became more common, and today the sandwiches are a common street food in Vietnam, and a staple of any Vietnamese restaurant in America.

Bánh mì served at my favorite Vietnamese restaurant in Minneapolis, Quang

Bánh mì served at my favorite Vietnamese restaurant in Minneapolis, Quang

In the book Ethnographies of the State in Central Asia, Alima Bissenova categorizes the Kazakh officials’ strategy in building Astana into a modern capital as borrowing cultural capital from Western cities and brands. This means prioritizing building luxury malls and imposing architectural projects designed by Western architects. This strategy, however, only creates economic capital, and doesn’t do anything to enhance the local culture (128). It is only after people begin to live in the city and develop their own sense of identity that this economic capital is developed into real cultural capital. Opening a massive luxury mall or a Ritz-Carlton in Kazakhstan brings in an aspect of foreign culture, but doesn’t really contribute anything to the local scene. When the first McDonald’s opened in the Soviet Union, it had a similar effect of making the country feel more modernized, because of the Western cultural capital it brought with it. Restaurants, however, tie people together in a way that malls don’t. The first McDonald’s in Soviet Russia allowed people to experience Western culture firsthand, and created a sense of brotherhood with America that reflected the tail end of the Cold War. Today in Russia and in Kazakhstan, eating fast-food burgers is completely normalized, just as eating sushi is in America. I think that over the next few decades, as more young entrepreneurs who’ve grown up eating both Central Asian and Western food decide to start restaurants in the region, there’ll be a surge of restaurants that bring together these cuisines in a more meaningful way, and greatly evolve the culinary future of Kazakhstan.

All images in this post were taken by me, and may be reused under the CC-BY 4.0 license.